Gresham Fernandes writes about nose-to-tail, the joys of letting a stranger order for you at a restaurant, and the many ways to kill a crab. Gresham is the Executive Chef at Impresario Hospitality (Smoke House Deli, The Social and Salt Water Café), and is also the designer behind their many supper projects including Swine Dine. A communal dining event held in Delhi, Bangalore and Mumbai, Swine Dine typically spans 13 courses that celebrate pork, and allows Gresham the creative license for culinary experimentation, that a more traditional restaurant format might not afford. He has also been part of an exclusive culinary residency program at Noma, the internationally acclaimed Michelin-starred restaurant in Copenhagen. As Swine Dine turns five, we get Gresham to look back at the beginning.

People often ask me, “Why Swine Dine?” and I always reply, “Why not?” Time slows down when you cook for family, friends and like-minded folk. It’s a different kind of cooking, unlike the sort of cooking that goes on in a high-pressured commercial kitchen where there are 300 things to keep track of.

Swine Dine, like the name suggests, is centred around pork, but I wouldn’t call it a theme-based dinner – I cook dishes I haven’t eaten in a while, or recreate a recipe that stayed with me from travels through a market. We’ve done a Chinese dinner with pork buns and Sriracha, bacon and chorizo fried-rice, belly braised in XO sauce, tapioca pudding with jaggery, caramelized bacon – the works! Another time we designed an Indian Swine Dine – biryani, galauti and haleem. (A lot of people considered it insensitive. I gave it some thought, and asked my right-hand man, Manoj, what he thought. Would we hurt too many sentiments? He replied with, “Fuck it, lets do it.” And the rest is history.)

Swine Dine is also about allowing people a peek into my past, into what my mother and grandmother cooked and fed their families. It is an insight into seasonality and affordability, with nothing going to waste; leftovers were shared with neighbours because refrigeration was practically non-existent. Even the street dogs feasted on the bones.

THE DINING TABLE

The one thing that has remained a constant in my life is the role of the dining table. Back at my grandmother’s, the table was the most-used piece of furniture; pigs and hens were stuffed here, vegetables prepped, meals eaten, grandchildren put to sleep, love letters written, hearts broken. Everything revolved around this table. I still remember the rough marble top with its stains and grooves, from the banging when crabs were in season. The weapon of choice varied with the person in charge of killing the crabs – locks, stones, sometimes the back of a cast iron pan. No plates on the table – just newspaper; no conversation – just the sounds of cracking and slurping.

Meals had to be eaten together at the table; my grandmother was particular about that. Towards the end of her life, she practically ran the house sitting at that table.

Raw mango & pork curry, with aged sorpotel.

COMMUNITY DINING

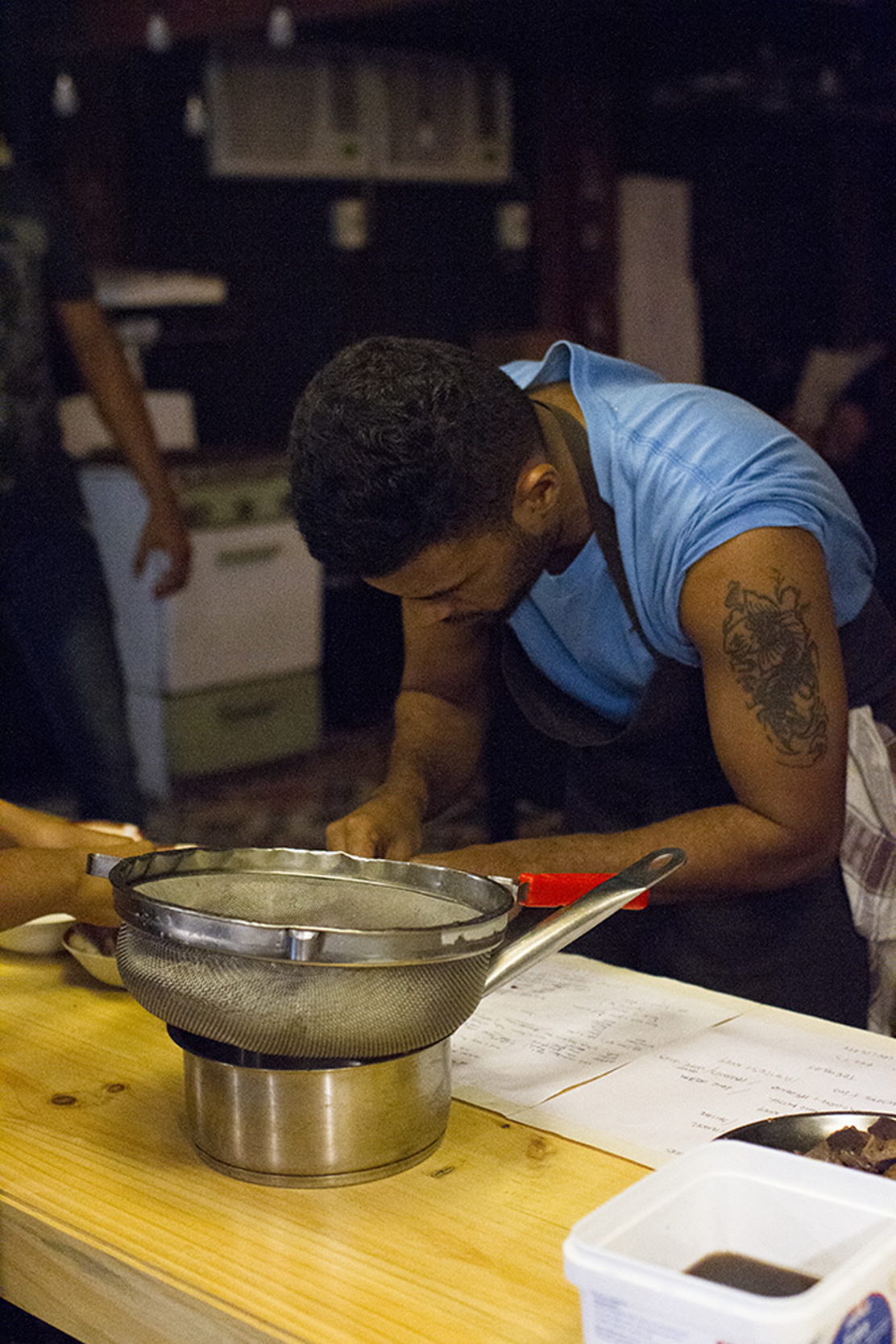

Swine Dine evolved to serve two purposes: cooking sustainably and cooking for the community. We wanted to create a setting where people could be loud, and be themselves, bound together by food. Remember when weddings were a village affair and not confined to just the family? Everyone came out to help prepare for the evening’s feast. It still happens in villages, but that’s a tradition lost in the big cities.

At Swine Dine we seat between twelve to thirty people (depending on the pig, and what the market has to offer on that particular day). Although Swine Dine caters to a large demographic, very often it is people who are new to the city, with no family and few friends. This was part of the vision for Swine Dine – we wanted to have strangers come share a table, and make new connections over food. Recently a couple celebrated their third anniversary together – they met at a Swine Dine, brought together by a love for pig.

But most people are not very open to canteen-style seating, where strangers sit next to each other for a meal. Perhaps it's because we’re not as tightly knit as a community, or because we don’t want to step out of our comfort zones. It works in dive bars and toddy shops, and I see it at my local bar all the time – old uncles discussing politics and football with the foreign exchange student who is alone, and has come to the bar because he knows that Bandra’s bars are the best way to get to know the city. When I look back at some of best meals I’ve eaten, it’s always been when I’ve let the stranger across the table order for me.

Sign up to experience community dining at the next Swine Dine in your city here.

GRESHAM’S PORK WITH SOUR THINGS

This is a dish that my dad learnt from his mother, or my grandmother who I’ve mentioned in the article. This would be the one dish I eat on my 'last day' - for lunch, that is; I have a different dish in mind for my last supper, but that’s a story for another time.

Ingredients

1 kg pork, freshly butchered in a curry cut, with fat, skin and plenty of bones for a rich stock.

2 dried raw mango seeds

1 ball of salted and fermented tamarind*, the size of a small plum, soaked in hot water and passed through a sieve. (In a pinch, you can use the packet variety).

1-inch ginger, julienned

3 cloves of elephant garlic, julienned

½ tsp turmeric powder

1 smoked bhoot jolokia (or 2 fresh green chilies, slit lengthwise)

1 tbsp unfiltered palm vinegar

Salt, to taste

Spice Mix

(Makes extra. Use the remaining on roasts, cutlets, or warmed with brandy and orange)

100 g cinnamon

40 g green cardamom

40 g cloves

15 g pepper

Lightly toast and grind well

Method – Day 1

Add all the ingredients to a pot with just enough water to submerge the meat, and 1 tablespoon of the spice mix. Bring to a boil. Skim the top for the grey goop that will surface. (This is just coagulated protein and blood).

Cover with a tight lid and simmer for 40 minutes, or until the pork is cooked through.

Check for seasoning. Cool and refrigerate.

Day 2

Bring the pork to boil on a low flame. Turn off the heat after 2-3 minutes. Cool and refrigerate.

Day 3

Repeat - Bring to boil on a low flame, and turn off after 2-3 minutes. Cool and refrigerate.

Note – This dish can be served immediately on day 1, but is best enjoyed a week after. The souring agents act as preservatives, and ageing allows the tamarind and vinegar to mellow and the flavours to deepen, as the dish thickens with melted gelatin from the skin and bones.

Serve hot with rice (preferably not basmati).

* Fermented tamarind is regular tamarind that has been de-seeded, rolled into balls, coated in rock salt and left to ferment for a few months.

Photos by Juhi Sharma.